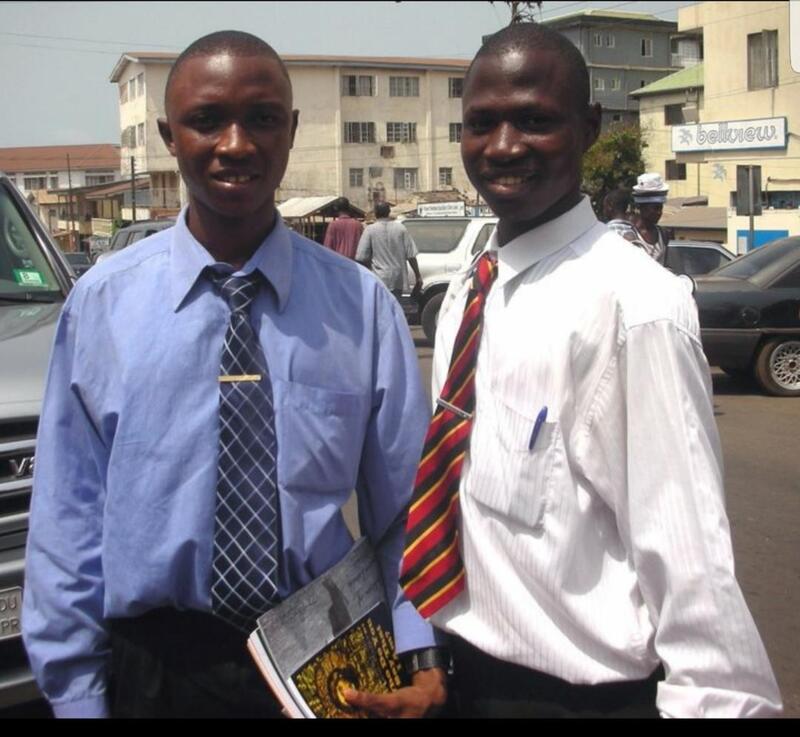

An interview with CRC alumnus Abdulai Swaray, one of the original 40 children rescued from the street during the Sierra Leone civil war. Today, Abdulai is an IT professional who lives with his wife and children in Maryland. He is currently searching for a job opportunity in information technology, cloud computing, cybersecurity, system analysis, or database administration. I was born during the 'Blood Diamond' war in Sierra Leone, West Africa, in a village in Pujehun district. To escape the war, my parents took me into the jungle where we lived for several years. The rebels eventually found us in the jungle and I was separated from my parents. I followed a convoy that led to the city, and I ended up in Bo city without my parents. I struggled in the city without them. I even entered into child labor and began sleeping on the street and living off the food I found. I was rescued from the street by the Child Rescue Centre, and lived there until I graduated high school and went off to university. In 2012, I got married to the love of my life. God blessed us with a child, and I had the opportunity to travel to the United States on a full scholarship from Ramapo College where I earned my bachelor's degree in Information Technology Management. In 2018, God blessed us with another child. Juggling work as a dad and husband, I pursued a Master's degree at George Mason University in Applied Information Technology. In 2020, I earned my MS degree with a concentration in cyber security. During my senior year of high school, I founded an organization called Young Vision Africa to empower young leaders in developing nations to achieve sustainable change in their communities. YVA provided housing, education, clean water, and health services to vulnerable people in West Africa, and we recruited American sponsors to join in these efforts. My involvement with YVA provided me the opportunity to speak globally about issues and challenges in Africa, including the Ebola crisis, and I was a featured speaker at the opening ceremony for Ramapo College's 'Year of Sub-Saharan Africa.' Those we are serving are at the center of everything we do." In 2017, I became an ambassador for one of my dream projects, "Healthcare Without Borders" at Thaakat Foundation. We have established two healthcare facilities, treated over 18,000 patients, and delivered more than 450 healthy babies. We continue to develop programs to aid in the overall quality of life for communities in Pujehun District. We manage malaria prevention and treatment programs and have an acute malnutrition program to assist the under-five population. As an ambassador, I helped the Foundation navigate through challenges, keep them focused, and ensure that those we are serving are at the center of everything we do. I am also a board member with Unsilenced Voices, a nonprofit whose mission is to help victims of domestic abuse and gender-based violence worldwide.

1 Comment

Even as a small boy growing up in Gbeworbu, a rural village in the Pujehun district of southwestern Sierra Leone, Aruna showed great academic promise. His widowed mother, recognizing her young son’s potential, pleaded with a friend in Bo to take Aruna, so he could go to a better school.

“Where I came from, we had no doctors, only community health assistants who came on outreach from Bo. I remember when we went to the doctor, we had to queue for a very long time to get treated,” Dr. Aruna Stevens says. “I decided I had to become a doctor so I can help people. We cannot only have doctors in the city.” In Bo, Aruna lived in a crowded, noisy communal home with his mother’s friend, Fatmata, who made her living selling street food in the park. He attended Ahmadiyya Primary School, where he excelled despite the harsh circumstances. Before and after school, Aruna was expected to work to earn his upkeep and his school fees. “I only got to eat after selling,” he remembers. “What remained is what we eat. I never had time to study. We had to prepare food early in the morning, and I was always late for school.” It was a hard and lonely life for a small boy, far from his home and family. Aruna’s life changed forever when the Child Rescue Centre, newly launched to rescue orphaned and abandoned children from the streets of Bo, identified him as a child at risk. With his mother’s permission, he was brought into the residential centre. “At the first interview, they asked me ‘what do you want to become?’ and I said, ‘a doctor who gives injections.’” The CRC was a radical departure from his former hard scrabble life, Aruna recalls. “At the CRC everything was different. I had my own bed. I used to sleep on the floor when I stayed with my auntie. At the CRC, I had three square meals a day.” In the stability and structure of the residential home, Aruna applied himself relentlessly to succeed in school. “After study time when I got to my room, I would do an extra two hours of reading and studying. When we had time to play, I used some of my play time to study. I tried to stay ahead of my class. I created additional time for my studies.” “What motivated me to do that?” he asks himself. “I have a family and I really love my mom. I have three sisters. I’m the eldest. I had to be somebody who takes care of my family, and be someone who can help people.” Aruna recognizes both the benefits and drawbacks of growing up in a residential home. In the CRC, he was protected from the dangers of street life. “It is getting difficult for [kids today] because of the advent of social media and distractions. I was totally protected. Kids don’t have these protections. At the CRC your day is very structured, on the outside it is not,” he observes. On the other hand, he missed his family. “Even though the CRC gave us clothing, food and everything, the family connection was not there. You had many brothers at the CRC, but you sit alone and you miss some part of you, even though you have everything. I love my mom, even now I think about her every day. But I don’t have that connection with her because I didn’t see her for so long…I never had the chance to really connect with her on the level of mother and son.” Aruna felt a separation between kids in the community and the kids at the orphanage. “Some boys looked at us as special, and teachers treated us differently. You want to blend with your colleagues and be treated like any other kid, but some people treat you differently. People expected a lot from us,” he remembers. Aruna graduated Senior Secondary School and was accepted to the premedical program at College of Medical and Allied Health Sciences (COMAHS) of the University of Sierra Leone in Freetown. At first, he found it difficult to adjust to life outside of the residential centre. “Adaptation was the big gap. At the CRC every need is met, and all my fees paid, so it was very easy. When I went to university, I had to find a place to stay. I used to get three meals at the CRC, and we had light from the generator. Teachers came and gave us extra classes. It was a new world after the CRC. Now I had to find my own food. Where I stayed there was no generator, so I had to buy candles to study. In the CRC, my day was planned. Now, I had to prepare,” he says. He recognizes that it is hard for young people to make the transition from residential home to community life. “Most kids who transitioned from the residential home to family care could not easily adapt to these changes. It was only with the help of God that I could come through these problems.” Finishing medical school was the biggest challenge he has faced so far, Aruna says. “Studying medicine in Sierra Leone is very difficult compared to other places. The first and second years of medical school were really tough. We were shouted at all the time and not encouraged, emotionally tortured. You don’t get the self confidence that you can do things. I felt like I could quit. Somebody suggested ‘Can you switch to something else?’ There are other ways, but if you have a goal, you have to work towards it. Beginning with the end in mind, I wanted to help my country,” Aruna says. He graduated medical school in 2018 and finished his housemanship (residency) in March of this year. Mercy Hospital quickly seized the opportunity to hire Aruna, and he was happy to return to Bo, the place he considers his home. “Working at Mercy Hospital is a dream come true,” he says. Aruna was the only graduate from his class who wanted to serve in a semi-rural area. “People in Freetown have better medical care, more doctors,” he says. “I graduated with 36 people and they all stayed in Freetown, except for me. The problem is when they come to the provinces they get deprived from all the fancy things they enjoy in the city.” He is willing to forego the advantages of city life for the gratification of caring for an under served population. “If I treat people in Freetown I never see them again. If I treat someone in Bo, they are my people. Some of them knew me before and they never believed in me. They say, ‘He’s very young.’ But by the end of the day they say ‘Oh, I am grateful you are here,’” he laughs. Aruna says the most prevalent medical concern he sees at Mercy is metabolic disease, which he believes is caused by poor diet and the lack of health information among a predominantly poor and illiterate population. “During my final year in med school, my research was on disease patterns presenting at Connaught Hospital, the main ICU in all of Sierra Leone. Non-communicable disease is on the increase with high mortality. People die in Sierra Leone from what should not kill them, things that could be prevented by health education. People get to the hospital very, very late.” He wants to help change that through improved health education and preventive measures. “My primary aim is to reach out to people. I don’t want to be the doctor who only treats them for their condition and never sees them again, I want to help them take care of these co-morbidities before they get so sick. We have people who are diabetic, or have hypertension, who don’t know how to take care of themselves. We could train medical students and nurses to go out and take people’s blood pressure and teach them how to take care of themselves. I’ve always been yearning to do this.” Children’s health care poses a different set of problems, Aruna observes. “For children, the chief complaint is malaria and its complications. When I did rural postings, we saw a lot of kids with hernias. The abdominal wall is weak from kids lifting heavy loads.” Aruna is so grateful for the opportunities he has been given, but he wishes he were closer to his family. “Ten years ago, if they asked me where I want to go, I would say the orphanage. Now, looking back I would love to stay with my family, if my needs could be met. I would love to be connected to my family.” One of his sisters is studying for a degree in business administration, and another is studying financial administration. “My mom is doing good. Now I’m thinking she could relocate to Bo. I last saw her at graduation. She had so much faith in me – she knew I could do anything,” he remembers fondly. Brian McCaffrey, Aruna’s long time sponsor through Helping Children Worldwide, was so happy to learn about his appointment to lead doctor at Mercy Hospital. “I smiled ear to ear as I read [the news],” Brian wrote. “What a wonderful opportunity for him to give back to his local community, while also serving as a role model to the current CRC students of what they can aspire to.” Aruna is enjoying the opportunity to reconnect with the community. “I happened to visit one of my teachers who taught me in class three. I met her three weeks ago and I told her ‘I’m a doctor now’ and she was so surprised. She always tried to motivate me. I had to introduce myself to her, but then she remembered me!” “For me, it’s a joy to work with the people that saw me growing up. It may not be what I anticipated, but it is good to be back home,” Aruna says. “If you have a goal, you can work towards it,“ he says in conclusion. “Not everyone needs to go to medical school, but everyone needs to read and write. Because a medical doctor is not the only way up. There are many opportunities.” |

Follow us on social media

Archive

July 2024

Click the button to read heartfelt tributes to a beloved Bishop, co- founder of our mission!

Post

|

Helping Children Worldwide is a 501 (c) 3 nonprofit organization | 703-793-9521 | [email protected]

©2017 - 2021 Helping Children Worldwide

All donations in the United States are tax-deductible in full or part. | Donor and Privacy Policy

©2017 - 2021 Helping Children Worldwide

All donations in the United States are tax-deductible in full or part. | Donor and Privacy Policy