|

Two years ago, HCW Partner Church Ebenezer UMC committed to partner with Fengehun village to provide desperately needed clean water and sanitation solutions to the community. Initially delayed by country-wide COVID restrictions, the projects are now well under way in the capable hands of Elmer and Joann Reifel, missioners with Christians in Action Missions International who are based in Bo, Sierra Leone.

A major part of the Reifels’ work in Sierra Leone is providing clean water to communities in need via hand-drilled boreholes. Elmer is also an ordained minister who serves as CinA’s Africa Area Director. The Reifels use every opportunity to share the Gospel whenever possible. The Reifels’ work with Helping Children Worldwide began in 2018 when former HCW Field Director Kim Nabieu engaged them to drill wells in two small villages, funded by contributions made to HCW on behalf of a retiring Methodist minister. With the launch of the Village Partnership initiative, HCW asked the Reifels to submit a bid for wells and latrines that were needed in Fengehun, a village served by Mercy Hospital’s mobile outreach team. During a 2019 mission trip to Sierra Leone, Ebenezer UMC Pastor Rob Lough and Missions Director Tina DeBoeser met with Fengehun leadership and committed to a partnership between their church and the village. The projects were supposed to be completed in 2020, but COVID closures delayed the start until February of this year. The Reifels have completed the new fresh water well and have finished refurbishing the two older wells. They also began work on a new three-stall latrine. After the Fengehun projects are complete, they will begin similar projects in Lemblema, the site of another Village Partnership project. "We are pleased to let you know that the new well, the first on our list of to-do's in Fengehun, is complete and fully operational," Joann Reifel reported. "The pump base was installed in the new concrete base last week and given about four days to cure before installing the rest of the pump and shocking the water to purify it for drinking. A yield test allows us to gauge whether or not there is enough water coming into the hole to use a pump, and we do that before we commit to installing a pump. The yield of this well is a terrific 10.8 gallons per minute, so it should be able to keep up to the demand. " "The method we use for the drilling of the borehole is a manual drilling process using a variety of augers, cutters, rock breakers and tips depending on local geology," Joann explained. “The new pump parts were installed in the original standpipe and the water source is protected now from the parts of the well that were collapsing in on it and causing the mud to build up over the years." The new pipes also go further down than the old ones, allowing the villagers to pump water even during the dry season. The new and renovated wells should supply Fengehun village with clean, fresh water for many years to come. When the new latrines are completed, the village will be a healthier and more hospitable place for the residents.

0 Comments

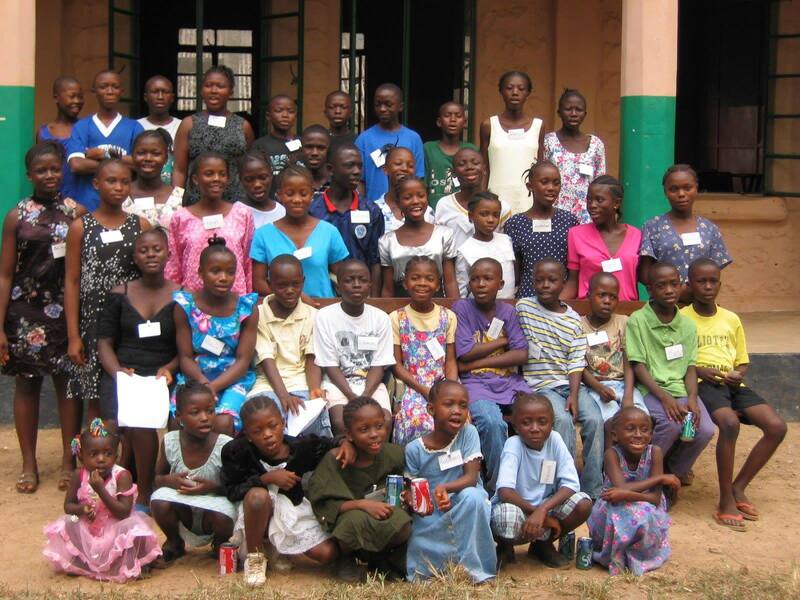

The Servant Heart Research Collaborative, a project of the University of Maine Honors College, developed a six-part series of workshops on attachment theory for caregivers of displaced, orphaned, and extremely vulnerable children. The following panel discussion with Dr. Laura Horvath, UMaine alumna Patty Morell, and the members of the SHRC details the history, development and implementation of the attachment theory workshop series, and how it is impacting vulnerable families in Sierra Leone. Of the many family strengthening workshops and programs provided by the Child Reintegration Centre (CRC), the jewel in the crown of the series is the Attachment Theory Workshop and Self-Paced Refresher Training, or AT Workshop. This six-module series is taught to caregivers whose children are enrolled in the CRC programs and in similar programs in the Kono District, and helps caregivers understand the impact of trauma on children and how it can affect their behavior. Each module provides practical tools that help caregivers form loving, healthy, and lasting relationships with their children. Over three years, the AT Workshop has evolved and expanded to serve a widening pool of caregivers seeking to provide excellent care for children in their home. The workshop began as a tool to help train six CRC residential aunties to bond with the children living in the orphanage. Through the work of the students and faculty of UMaine’s Honors College, it has grown with the needs of the program and transformed into a curriculum that teaches parents and caregivers how to bond with the children being reintegrated into their families. It is also being used as a tool for parents whose children have never been separated from them to teach them how to bond better, and has been offered to over 200 caregivers in Bo alone. When the success of the initial AT Workshop was published, it sparked conversations among child welfare organizations all over the world, expanding first to other locations in Sierra Leone, including four areas in the Kono District (Ngaiya Town, Jesus Town, Sukudu, and Koidu), training an additional 160 caregivers in this region, and then beyond. The AT Workshop is being adapted for use by child welfare organizations around the world, who are hoping to pilot the workshop in their own organizations and locations. History In December of 2015, University of Maine alumni and long-time supporters of Helping Children Worldwide (HCW), Patty and Allen Morell reached out to Helping Children Worldwide’s Director at that time, Ginny Wagner, with a request to develop a list of projects that could help address needs at the CRC. These projects would be undertaken by a group of undergraduate students at UMaine’s Honors College, guided by faculty mentors. Alli DellaMattera, one of the undergraduate students who created the AT Workshop, now leads the efforts of the Servant Heart Collaborative at UMaine that is continuing to work on curriculum development for use in the cultural context of other countries. UMaine students Grace, Alli, and Alex each used their work on the AT project in their final Honor’s theses. Giving these students the opportunity to see themselves as powerful agents of change was equally important to the Morells. Of seven ideas proposed, one was to research and “develop a year-long (6-12 lessons) curriculum (for a resource scarce environment) to teach caregivers” to establish healthy bonds with their children who’d suffered trauma. Lessons would include theory and application, with role playing as a key component of skill building, and were initially conceived to train the residential staff of the CRC orphanage. Patty Morell: Allen and I are quite active as alumni on different projects that connect and encourage both students and faculty to get involved with volunteerism, including research and projects that produce solutions that meet challenges locally, nationally and internationally. We [felt] it [was] key that students understand volunteering their time, talent and resources is an important part of university life and becoming a valuable member of society. Because of our own long-time commitment to the CRC, it was a natural progression that we wanted to connect the University of Maine with Sierra Leone in meaningful ways. Dr. Melissa Ladenheim: When I first met with Patty and Allen, they communicated that their desire to partner with UMaine was fundamentally driven by two motivations: 1) to bring the capacities and resources of UMaine to help Sierra Leone solve some of its problems, and 2) to enable undergraduate students to understand their privilege and their own capacity to be powerful agents of change. Most importantly, Patty and Allen wanted me to know that the Sierra Leoneans themselves understood good solutions, but lacked resources and sufficient bandwidth (literally and figuratively) to implement them. I was approached to meet with Patty and Allen because of my history of social justice work with UMaine students. I was interested in hearing about the Morell’s work because of that, and also because I had been a founding member and mentor in another successful research collaborative in the Honors College, so I had experience and confidence in this model. As well, I felt that Honors, with its interdisciplinary body of students and faculty, with its curriculum that asks students to grapple with big questions (such as: What are our obligations to others? How should we live? How do we create a just world?), and its goal of cultivating critical thinkers and informed citizens, was a perfect home for this partnership. Once the Morells shared the list from HCW, I undertook recruiting students and faculty to the projects. I didn’t select the AT Workshop from the list; in the end that choice arose in some ways serendipitously from the interests and skills of the students I recruited along with what seemed most possible for us to accomplish. I pulled Julie in fairly early in the process. Julie Dellamattera: I feel so incredibly fortunate that Melissa thought of me once the AT project was decided upon. I remember sitting in her office as she started her “pitch” for a faculty mentor. She was only about 2 minutes in, when I remember thinking to myself, “Yes! Oh, please let me be a part of this!” The idea of supporting students to be part of something bigger than themselves was so appealing. And the topic was right up my alley both professionally and personally. I teach aspiring educators and those who want to work in agencies supporting kids and families. The cornerstone of what I espouse is attachment and respect and to be able to help undergrads from a variety of backgrounds and majors spread that message was something I couldn’t say no to. Dr. Laura Horvath: From the HCW/CRC perspective, the selection of the AT Workshop was ideal for that point in the life of the CRC. We knew that the children living in the orphanage had suffered trauma; becoming separated from parental care is itself a trauma, but these children had suffered additional traumas - that’s what led them to placement in the CRC programs to begin with. We understood that teaching the staff how to form healthy bonds with the children would help heal some of that trauma. Melissa: From the UMaine perspective, we had multiple goals and outcomes in mind as we embarked on this project. We wanted students to work on meaningful projects, that the work they did would be empowering and their contributions valued, that they would see what they could contribute and the implications of that work, that it could potentially lead to a thesis project (which it has for three students who worked on AT), that they learn about working on and being part of a team, and that there was an appreciation for the contributions of a number of different perspectives and disciplines in problem solving. The workshop was originally created as a training for the orphanage staff working directly with the children living in the orphanage. When a decision was made in Sierra Leone to transition the orphanage program to a family-based model that would reintegrate all of the children living there back into family-based care, a change in the approach to the workshop design became necessary. Melissa: The changes at the CRC from a residential facility to a family-based one had an impact on what we were doing, and so learning to be flexible and how to pivot strategically also turned out to be good lessons. As well, it became clear part way into the work that the best course of action for our team would be to build our own training based on research and best practices as reported in the literature, and I think this was absolutely pivotal for this project. Laura: When the decision was made to reintegrate children who had lived for years in the orphanage back into families, we knew that there would be a gap in the caregivers’ capacity to form healthy attachments with the children they were receiving into their homes. The research is clear that children grow and thrive better in loving, permanent families, but it’s not a simple matter of just placing a child with a family. Families have to be prepared for reintegration, and parents and caregivers of children suffering from trauma need training and tools for how to relate to each other and build healthy attachments. Parents needed to understand why their child might behave in certain ways, and children who’d never formed a long-term attachment to a primary caregiver need to be helped to do that. It was important to equip the parents. Melissa: The pivot was pretty seamless in some ways because the basic idea of offering support to a caregiver was fundamental, pretty much regardless of the setting for the caregiving. Laura: Right - the caregiver was either the orphanage staff/Auntie, or it was the parent. Same principles apply. Melissa: There were additional considerations, of course, as the Aunties, by virtue of working for the CRC, came with a set of experiences, skills, and knowledge that could not be assumed in the family-based settings, so really thinking about who these people are and what they were bringing to the table did influence (to greater and lesser degrees depending on the concept and action step) the word choice and activities of the workshop as we adapted to this new audience. We had to imagine a range of literacy skills, for example. Laura: This has turned out to be one of the workshop’s greatest strengths, in my opinion. In HCW’s global advocacy work, we’re connected to many programs around the world, lots of them have trauma-informed training similar to the workshop. The difference is that the vast majority of them are designed for staff - social workers - who are mostly literate. The AT Workshop is the only one I know of that is designed for caregivers who don’t need to be literate at all. Additionally, rather than training social workers, the focus is on equipping the caregivers and parents whose children have suffered from trauma, to empower them to parent their children well. This builds not only the capacity of the caregivers, but empowers entire families. Melissa: There are some key points that are fundamental to the success of the AT project, and perhaps the most important one, to my mind, is the intentional creation of partnerships in Sierra Leone. When I first spoke with the Morells and better understood their role/relationship to the CRC, we agreed on the importance of also having community partners in Sierra Leone whose insider knowledge and cultural competencies were absolutely essential to our success. Laura: And this is another of the workshop’s greatest strengths. The process you used to work collaboratively and iteratively with the CRC staff on the ground to create something that is grounded in research and best practice but also incorporates the skills and knowledge of the CRC staff who helped create and use it, with a deep cultural understanding is huge. Even down to the tiniest detail - that the photos in the presentation look like the people in the audience, it really helps participants to ‘see themselves’ in the workshop, and feel like the concepts it teaches apply to their lives. Julie: We realized early on that as many of the adults speak and read only basic English that the photos were even more important. The photos are in essence visual touch points for remembering key concepts. If the photo resonates with the caregivers then, even if they cannot read the information, they can connect with the information visually. Alli: The CRC staff were an integral part of developing a workshop that really spoke to, and was relatable, to the caregivers that the training was intended for. To put it simply, we are not experts on Sierra Leone nor it’s people and despite the numerous hours of research we did to educate ourselves on daily life in Sierra Leone, cultural values, historic and present day traumas, etc., we knew the best people to give input, feedback, and suggestions on the AT Workshop were going to be Sierra Leoneans themselves. Julie: As a faculty mentor, it was amazing to see that the student team immediately realized that not only were they not experts on Sierra Leone, but also that they did not want to impose their privileged, white view about how best to raise children upon people from a culture very different than ours. This self-awareness and, dare I say, very mature view, set the foundation for deeply appreciating the collaborations and partnerships created in Sierra Leone. Melissa: The iterative nature of the work is one of the most important pieces here in my mind as it speaks to the value of partnerships with all the stakeholders represented. Being able to work with David, Amie, and Deborah (CRC Case Managers), and later others on the CRC staff, and get their input strengthened the quality and effectiveness of the training, and ensured they were a good fit for the audience. Laura: And now the curriculum is traveling outside of the borders of Sierra Leone. Pilot projects are underway in Haiti and Uganda, and interest continues to grow. The best part of watching these take off is that you continue to apply this deeply collaborative, iterative approach with new partners. Photos, terms and vocabulary from the existing CRC version are currently being adapted so that Haitian and Ugandan caregivers can see themselves in the materials. I have such deep respect for how closely your team works with these new partners to incorporate their thoughts and culture into their version of the AT Workshop, while still preserving its integrity. Melissa: The curriculum continues to evolve and be refined in an ongoing, iterative process that engages all of the members of the AT team, both in the US and in the local communities in Sierra Leone using the curriculum. The AT team completed a revision of the curriculum being used by the CRC just this spring, and we’re excited to be partnering with Helping Haitian Angels, and potentially other organizations working to reintegrate children from their orphanages back home with their families. Alli: When organizations are expressing a potential interest in the AT Workshop, I think it is so important for them to understand that we want honest, upfront, and raw feedback from their team based in-country so we can make the necessary changes in order for their participants to get as much as they possibly can from participating in the training. A goal of this training is to build better, healthier relationships between a child and their caregiver; and we are willing to make edits to the modules to ensure the best opportunity to reach this goal. Julie: Another part of the feedback process is that we are not only editing and refining the training but we are hoping to help answer the call of “we want more!” that we are hearing from parents and caregivers. The team is in the process of creating an at-home component to the training. We are currently working on a handout that attendees could take home at the end of each session with activities that could be practiced at home with the children and other family members. Some of these might simply be reminders for how to behave like, “Remember to breath and wait until you are calm to talk with your child” and others will be actual activities that will promote collaboration and attachment among family members. Laura: It’s amazing to me that this elegant and simple solution to meet a need at the CRC has grown and continues to grow. The AT Workshop continues to pivot to meet the needs of an expanding population beyond what any of us could have imagined. Julie: This entire project has taken us all completely by surprise, on so many levels. I know I had no idea the profound effect this would have on me and my life. We’ve been fortunate to go to Sierra Leone and meet the people whose lives have been changed by our training. As we sat at tables and listened to their stories of family transformation, as they grabbed our hands and thanked us, as we met smiling children - we cried tears of joy. And the crying has not stopped. Every time the AT team meets with Laura we all end up in tears; crying because we are so moved and happy and feeling blessed to be a part of something that has changed families in Sierra Leone and has the potential to change the lives of children everywhere. The impact our training can and may have is exponentially bigger than anything we could have foreseen or dreamed of. It takes my breath away. This article originally appeared in the HCW December 2020 magazine.

I told my family I would become an engineer so I could help rebuild." In Abdulai Sumaila’s home village of Bumpeh,a small town in the southern province of Sierra Leone, most families survive on subsistence farming, as they have for decades. Farming is the mainstay of rural families who mostly grow rice and cassava for their own consumption (Source: USAID.) In Bumpeh, school was not a high priority for children, who are needed to help in the fields. Abdulai and his five siblings enjoyed a simple life with their parents, who augmented their meager farming income by teaching and petty trading.

When the chaos of the civil war came to Bumpeh, Abdulai and his siblings were separated from their parents, leaving them to be raised by various relatives who used them for farm labor. “I would wake up at 4 AM and go to the farm,” Abdulai remembers, “I could only return back home in the evening.” During that desperate time, the family was focused solely on survival. School was out of the question for the children. Eventually the siblings learned that their parents had died, and their uncle and grandmother took sole responsibility for them. When the war finally ended in 2002, a field supervisor from the newly launched Child Rescue Centre (CRC) who had an affiliation with Bumpeh came there to investigate the welfare of the children. Most of the villagers were desperately poor and wanted their children to go to the CRC, where they believed they would have a chance at a better life and the opportunity to go to school. “In the village there were a lot of children in need. The only chance I had over the rest of the children is that they saw potential in me,” Abdulai says. After many meetings with the village chieftains, it was decided that seven children from the neediest families would go live in the CRC’s residential program, including 10-year-old Abdulai, who was the youngest in his family. Abdulai’s uncle vehemently opposed his admission to the CRC. But Abdulai’s grandmother wanted him to go to school and her will prevailed. Abdulai became one of the original 40 children taken in as residents at the CRC. In spite of missing several years of school, he skipped ahead to Class 3, then skipped again to Class 5. After passing the National Primary School Examination with a high score, Abdulai was admitted to the prestigious Christ the King College, an all-boys school near the CRC, along with several other CRC boys. In many ways, Abdulai loved his new life in the residential centre, and his memories are mostly happy. “Growing up at the CRC my life was full of curiosity and innovation,” Abdulai says. But he missed his family and the warmth of the village community. “The lifestyle [at the CRC] was very different,” he says. “A lot of the things I enjoyed with my family weren’t available, like gari (cassava meal) and kanya (peanut sweets.)” More than anything or anyone else, he missed his grandmother, the one who always believed in him. “My grandma was the only one I felt close to and she couldn’t afford to come to the city,” he says regretfully. Sadly, she died four years ago. “I’m very sad that she’s not alive to enjoy the benefits of me going to the CRC. What my family thought was evil turned out to be for good.” Abdulai is grateful for the opportunity he was given to get an education and pursue his dream, something he doesn’t feel would have been possible if he had stayed in Bumpeh village. “If I stayed with my family, I would have had no opportunities. My family lives far from civilization. And at the CRC, I got the opportunity to learn about Jesus Christ.” Of the six children in his family, he is the only one that went to school beyond the primary grades. “All of them quit by class 5 or 6 and ended up in farming or trading or mining,” he says. Growing up in the residential centre, Abdulai was aware that he was different from the other kids at his school, and he felt a keen obligation to become someone who could make a difference for his village of Bumpeh. “I felt a lot of responsibility. I got to visit my hometown and observed things that were very hurtful--the structure my family lived in, the famous bridge destroyed by the rebels in the civil war. The beautiful houses burned down. It made me think ‘who is going to rebuild these?’ The bridge in my home town was so dilapidated, residents can only use the boats to cross the water, and I’m a person who is very afraid of water! I told my family I would become an engineer, so I could help rebuild.” Propelled by that dream, Abdulai earned a scholarship to study civil engineering at Fourah Bay College in Freetown. Moving to the big city of Freetown was a major culture shock for Abdulai. “I was not too acquainted with the lifestyle or location. I had no clue where I was going. Everything must be planned and executed by me alone. Waking up early, cooking, doing laundry, and managing my own time. I was forced to embrace hard living outside the CRC,” he says ruefully. Abdulai met his wife, Aminata, through Navigators Christian Club at university. She graduated from Fourah Bay College with a degree in philosophy and law. They were married in 2019 and this year welcomed a baby girl to their family. “After graduating university, in Sierra Leone culture I became the head of my family,” Abdulai says. “I am holding to my dream to continue to provide quality professionalism in every task I am involved in, for the benefit of my country. I have worked as a supervisor on construction projects like hospitals, schools, commercial and residential structures on both a voluntary and paid basis. I hope one day I can be in a top national position, where I can use my technical skills and spiritual insights to transform the lives of others in Sierra Leone.” Abdulai wants to be a role model for young Sierra Leoneans, with this advice for the next generation: “Young people should believe in their dreams and work hard to see those dreams fulfilled. Know the Lord Jesus, be humble, and respect the older generation,” he says. His grandmother would no doubt be very proud of her grandson the engineer, who is helping rebuild Sierra Leone. This article originally appeared in the HCW December 2020 magazine. |

Follow us on social media

Archive

July 2024

Click the button to read heartfelt tributes to a beloved Bishop, co- founder of our mission!

Post

|

Helping Children Worldwide is a 501 (c) 3 nonprofit organization | 703-793-9521 | [email protected]

©2017 - 2021 Helping Children Worldwide

All donations in the United States are tax-deductible in full or part. | Donor and Privacy Policy

©2017 - 2021 Helping Children Worldwide

All donations in the United States are tax-deductible in full or part. | Donor and Privacy Policy