I told my family I would become an engineer so I could help rebuild." In Abdulai Sumaila’s home village of Bumpeh,a small town in the southern province of Sierra Leone, most families survive on subsistence farming, as they have for decades. Farming is the mainstay of rural families who mostly grow rice and cassava for their own consumption (Source: USAID.) In Bumpeh, school was not a high priority for children, who are needed to help in the fields. Abdulai and his five siblings enjoyed a simple life with their parents, who augmented their meager farming income by teaching and petty trading.

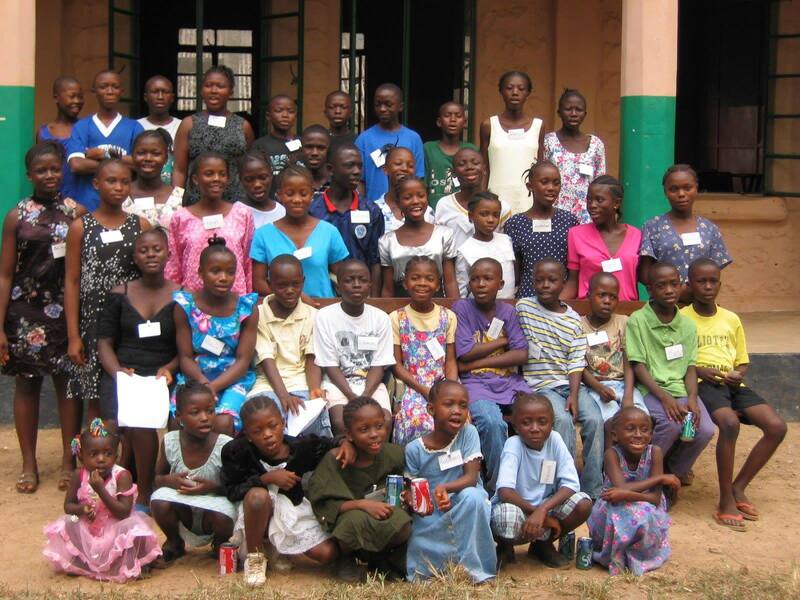

When the chaos of the civil war came to Bumpeh, Abdulai and his siblings were separated from their parents, leaving them to be raised by various relatives who used them for farm labor. “I would wake up at 4 AM and go to the farm,” Abdulai remembers, “I could only return back home in the evening.” During that desperate time, the family was focused solely on survival. School was out of the question for the children. Eventually the siblings learned that their parents had died, and their uncle and grandmother took sole responsibility for them. When the war finally ended in 2002, a field supervisor from the newly launched Child Rescue Centre (CRC) who had an affiliation with Bumpeh came there to investigate the welfare of the children. Most of the villagers were desperately poor and wanted their children to go to the CRC, where they believed they would have a chance at a better life and the opportunity to go to school. “In the village there were a lot of children in need. The only chance I had over the rest of the children is that they saw potential in me,” Abdulai says. After many meetings with the village chieftains, it was decided that seven children from the neediest families would go live in the CRC’s residential program, including 10-year-old Abdulai, who was the youngest in his family. Abdulai’s uncle vehemently opposed his admission to the CRC. But Abdulai’s grandmother wanted him to go to school and her will prevailed. Abdulai became one of the original 40 children taken in as residents at the CRC. In spite of missing several years of school, he skipped ahead to Class 3, then skipped again to Class 5. After passing the National Primary School Examination with a high score, Abdulai was admitted to the prestigious Christ the King College, an all-boys school near the CRC, along with several other CRC boys. In many ways, Abdulai loved his new life in the residential centre, and his memories are mostly happy. “Growing up at the CRC my life was full of curiosity and innovation,” Abdulai says. But he missed his family and the warmth of the village community. “The lifestyle [at the CRC] was very different,” he says. “A lot of the things I enjoyed with my family weren’t available, like gari (cassava meal) and kanya (peanut sweets.)” More than anything or anyone else, he missed his grandmother, the one who always believed in him. “My grandma was the only one I felt close to and she couldn’t afford to come to the city,” he says regretfully. Sadly, she died four years ago. “I’m very sad that she’s not alive to enjoy the benefits of me going to the CRC. What my family thought was evil turned out to be for good.” Abdulai is grateful for the opportunity he was given to get an education and pursue his dream, something he doesn’t feel would have been possible if he had stayed in Bumpeh village. “If I stayed with my family, I would have had no opportunities. My family lives far from civilization. And at the CRC, I got the opportunity to learn about Jesus Christ.” Of the six children in his family, he is the only one that went to school beyond the primary grades. “All of them quit by class 5 or 6 and ended up in farming or trading or mining,” he says. Growing up in the residential centre, Abdulai was aware that he was different from the other kids at his school, and he felt a keen obligation to become someone who could make a difference for his village of Bumpeh. “I felt a lot of responsibility. I got to visit my hometown and observed things that were very hurtful--the structure my family lived in, the famous bridge destroyed by the rebels in the civil war. The beautiful houses burned down. It made me think ‘who is going to rebuild these?’ The bridge in my home town was so dilapidated, residents can only use the boats to cross the water, and I’m a person who is very afraid of water! I told my family I would become an engineer, so I could help rebuild.” Propelled by that dream, Abdulai earned a scholarship to study civil engineering at Fourah Bay College in Freetown. Moving to the big city of Freetown was a major culture shock for Abdulai. “I was not too acquainted with the lifestyle or location. I had no clue where I was going. Everything must be planned and executed by me alone. Waking up early, cooking, doing laundry, and managing my own time. I was forced to embrace hard living outside the CRC,” he says ruefully. Abdulai met his wife, Aminata, through Navigators Christian Club at university. She graduated from Fourah Bay College with a degree in philosophy and law. They were married in 2019 and this year welcomed a baby girl to their family. “After graduating university, in Sierra Leone culture I became the head of my family,” Abdulai says. “I am holding to my dream to continue to provide quality professionalism in every task I am involved in, for the benefit of my country. I have worked as a supervisor on construction projects like hospitals, schools, commercial and residential structures on both a voluntary and paid basis. I hope one day I can be in a top national position, where I can use my technical skills and spiritual insights to transform the lives of others in Sierra Leone.” Abdulai wants to be a role model for young Sierra Leoneans, with this advice for the next generation: “Young people should believe in their dreams and work hard to see those dreams fulfilled. Know the Lord Jesus, be humble, and respect the older generation,” he says. His grandmother would no doubt be very proud of her grandson the engineer, who is helping rebuild Sierra Leone. This article originally appeared in the HCW December 2020 magazine.

0 Comments

Even as a small boy growing up in Gbeworbu, a rural village in the Pujehun district of southwestern Sierra Leone, Aruna showed great academic promise. His widowed mother, recognizing her young son’s potential, pleaded with a friend in Bo to take Aruna, so he could go to a better school.

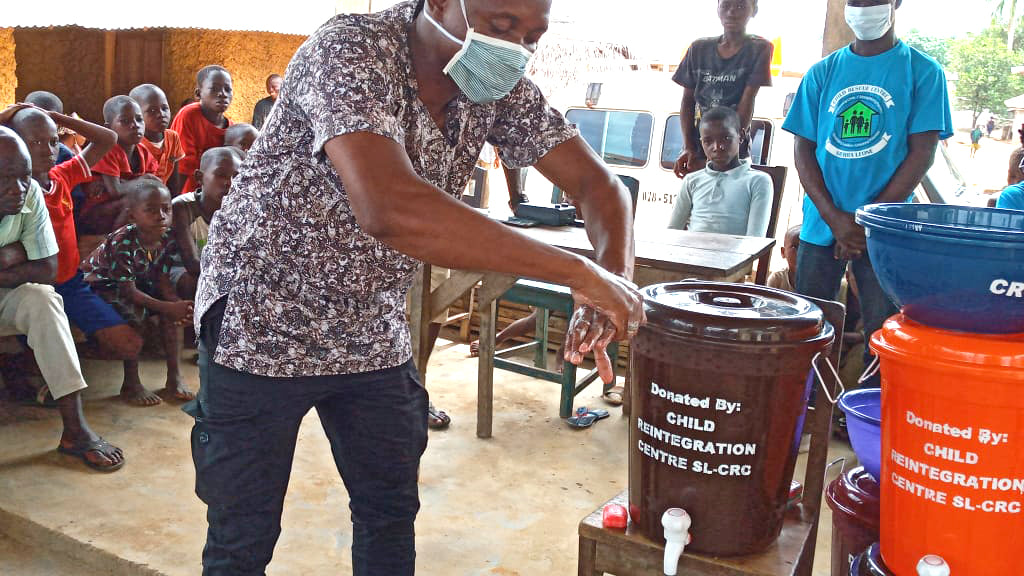

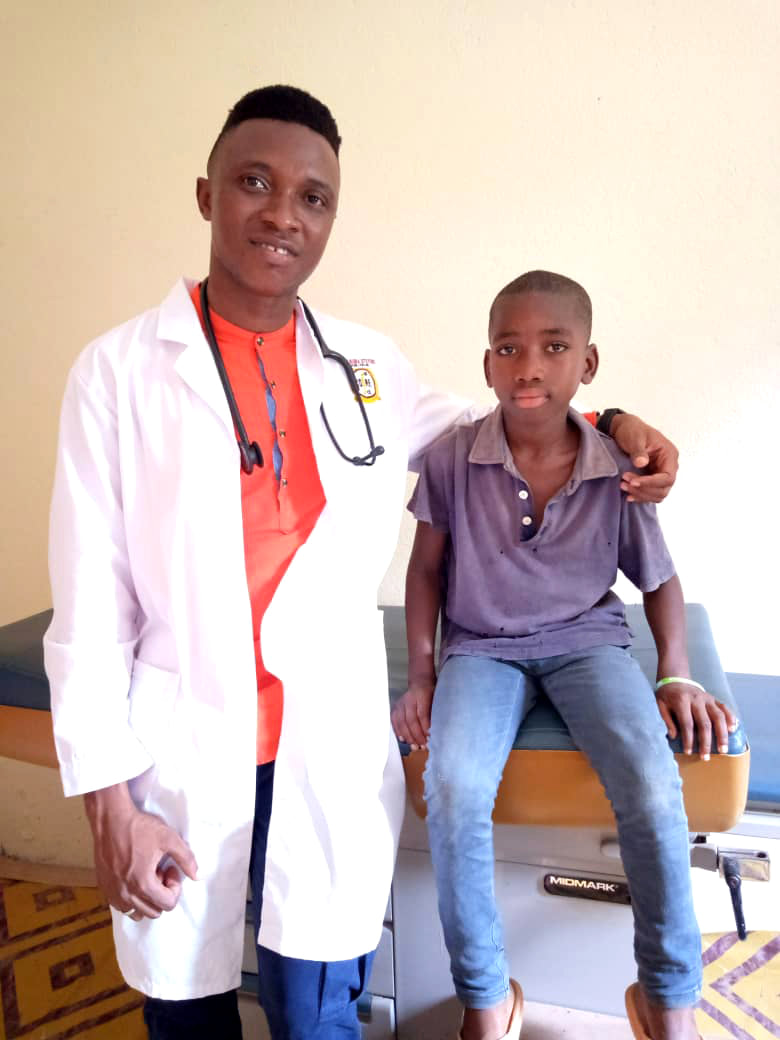

“Where I came from, we had no doctors, only community health assistants who came on outreach from Bo. I remember when we went to the doctor, we had to queue for a very long time to get treated,” Dr. Aruna Stevens says. “I decided I had to become a doctor so I can help people. We cannot only have doctors in the city.” In Bo, Aruna lived in a crowded, noisy communal home with his mother’s friend, Fatmata, who made her living selling street food in the park. He attended Ahmadiyya Primary School, where he excelled despite the harsh circumstances. Before and after school, Aruna was expected to work to earn his upkeep and his school fees. “I only got to eat after selling,” he remembers. “What remained is what we eat. I never had time to study. We had to prepare food early in the morning, and I was always late for school.” It was a hard and lonely life for a small boy, far from his home and family. Aruna’s life changed forever when the Child Rescue Centre, newly launched to rescue orphaned and abandoned children from the streets of Bo, identified him as a child at risk. With his mother’s permission, he was brought into the residential centre. “At the first interview, they asked me ‘what do you want to become?’ and I said, ‘a doctor who gives injections.’” The CRC was a radical departure from his former hard scrabble life, Aruna recalls. “At the CRC everything was different. I had my own bed. I used to sleep on the floor when I stayed with my auntie. At the CRC, I had three square meals a day.” In the stability and structure of the residential home, Aruna applied himself relentlessly to succeed in school. “After study time when I got to my room, I would do an extra two hours of reading and studying. When we had time to play, I used some of my play time to study. I tried to stay ahead of my class. I created additional time for my studies.” “What motivated me to do that?” he asks himself. “I have a family and I really love my mom. I have three sisters. I’m the eldest. I had to be somebody who takes care of my family, and be someone who can help people.” Aruna recognizes both the benefits and drawbacks of growing up in a residential home. In the CRC, he was protected from the dangers of street life. “It is getting difficult for [kids today] because of the advent of social media and distractions. I was totally protected. Kids don’t have these protections. At the CRC your day is very structured, on the outside it is not,” he observes. On the other hand, he missed his family. “Even though the CRC gave us clothing, food and everything, the family connection was not there. You had many brothers at the CRC, but you sit alone and you miss some part of you, even though you have everything. I love my mom, even now I think about her every day. But I don’t have that connection with her because I didn’t see her for so long…I never had the chance to really connect with her on the level of mother and son.” Aruna felt a separation between kids in the community and the kids at the orphanage. “Some boys looked at us as special, and teachers treated us differently. You want to blend with your colleagues and be treated like any other kid, but some people treat you differently. People expected a lot from us,” he remembers. Aruna graduated Senior Secondary School and was accepted to the premedical program at College of Medical and Allied Health Sciences (COMAHS) of the University of Sierra Leone in Freetown. At first, he found it difficult to adjust to life outside of the residential centre. “Adaptation was the big gap. At the CRC every need is met, and all my fees paid, so it was very easy. When I went to university, I had to find a place to stay. I used to get three meals at the CRC, and we had light from the generator. Teachers came and gave us extra classes. It was a new world after the CRC. Now I had to find my own food. Where I stayed there was no generator, so I had to buy candles to study. In the CRC, my day was planned. Now, I had to prepare,” he says. He recognizes that it is hard for young people to make the transition from residential home to community life. “Most kids who transitioned from the residential home to family care could not easily adapt to these changes. It was only with the help of God that I could come through these problems.” Finishing medical school was the biggest challenge he has faced so far, Aruna says. “Studying medicine in Sierra Leone is very difficult compared to other places. The first and second years of medical school were really tough. We were shouted at all the time and not encouraged, emotionally tortured. You don’t get the self confidence that you can do things. I felt like I could quit. Somebody suggested ‘Can you switch to something else?’ There are other ways, but if you have a goal, you have to work towards it. Beginning with the end in mind, I wanted to help my country,” Aruna says. He graduated medical school in 2018 and finished his housemanship (residency) in March of this year. Mercy Hospital quickly seized the opportunity to hire Aruna, and he was happy to return to Bo, the place he considers his home. “Working at Mercy Hospital is a dream come true,” he says. Aruna was the only graduate from his class who wanted to serve in a semi-rural area. “People in Freetown have better medical care, more doctors,” he says. “I graduated with 36 people and they all stayed in Freetown, except for me. The problem is when they come to the provinces they get deprived from all the fancy things they enjoy in the city.” He is willing to forego the advantages of city life for the gratification of caring for an under served population. “If I treat people in Freetown I never see them again. If I treat someone in Bo, they are my people. Some of them knew me before and they never believed in me. They say, ‘He’s very young.’ But by the end of the day they say ‘Oh, I am grateful you are here,’” he laughs. Aruna says the most prevalent medical concern he sees at Mercy is metabolic disease, which he believes is caused by poor diet and the lack of health information among a predominantly poor and illiterate population. “During my final year in med school, my research was on disease patterns presenting at Connaught Hospital, the main ICU in all of Sierra Leone. Non-communicable disease is on the increase with high mortality. People die in Sierra Leone from what should not kill them, things that could be prevented by health education. People get to the hospital very, very late.” He wants to help change that through improved health education and preventive measures. “My primary aim is to reach out to people. I don’t want to be the doctor who only treats them for their condition and never sees them again, I want to help them take care of these co-morbidities before they get so sick. We have people who are diabetic, or have hypertension, who don’t know how to take care of themselves. We could train medical students and nurses to go out and take people’s blood pressure and teach them how to take care of themselves. I’ve always been yearning to do this.” Children’s health care poses a different set of problems, Aruna observes. “For children, the chief complaint is malaria and its complications. When I did rural postings, we saw a lot of kids with hernias. The abdominal wall is weak from kids lifting heavy loads.” Aruna is so grateful for the opportunities he has been given, but he wishes he were closer to his family. “Ten years ago, if they asked me where I want to go, I would say the orphanage. Now, looking back I would love to stay with my family, if my needs could be met. I would love to be connected to my family.” One of his sisters is studying for a degree in business administration, and another is studying financial administration. “My mom is doing good. Now I’m thinking she could relocate to Bo. I last saw her at graduation. She had so much faith in me – she knew I could do anything,” he remembers fondly. Brian McCaffrey, Aruna’s long time sponsor through Helping Children Worldwide, was so happy to learn about his appointment to lead doctor at Mercy Hospital. “I smiled ear to ear as I read [the news],” Brian wrote. “What a wonderful opportunity for him to give back to his local community, while also serving as a role model to the current CRC students of what they can aspire to.” Aruna is enjoying the opportunity to reconnect with the community. “I happened to visit one of my teachers who taught me in class three. I met her three weeks ago and I told her ‘I’m a doctor now’ and she was so surprised. She always tried to motivate me. I had to introduce myself to her, but then she remembered me!” “For me, it’s a joy to work with the people that saw me growing up. It may not be what I anticipated, but it is good to be back home,” Aruna says. “If you have a goal, you can work towards it,“ he says in conclusion. “Not everyone needs to go to medical school, but everyone needs to read and write. Because a medical doctor is not the only way up. There are many opportunities.” The Child Reintegration Centre's education department, led by Education Manager Mabel Mustapha, organized a forum for secondary students to hear from successful graduates of vocational and technical programs. The forum aimed to remove the stigma students and their families may have towards vocational or technical training, and encourage them to seek successful careers in fields that don't require a university degree.

Daniel Lahai, a carpentry teacher at Sierra Leone Opportunities Industrialization Centers (SL-OIC), one of the CRC's approved post-secondary institutions, spoke to the students about training opportunities in the construction field. Mercy Hospital electrician Mohamed Bangura and CRC accountant Lucy Jusu shared their stories of personal success as graduates of votech programs who now have interesting, good-paying jobs with room for advancement. All three speakers attended SL-OIC before embarking on their current careers. Lucy worked for many years at the CRC before going back to school to earn an accounting degree. On a national level, the 2019 WASSCE exam results were very disappointing, and few students earned the scores required for university acceptance. Job training is an excellent alternative for senior secondary (high school equivalent) graduates. The most recent labor statistics from the World Bank show that just 10% of the population are wage or salaried workers, so good jobs are not easy to come by in Sierra Leone, but welders, electricians, accountants, and other skilled workers are in high demand. |

Follow us on social media

Archive

July 2024

Click the button to read heartfelt tributes to a beloved Bishop, co- founder of our mission!

Post

|

Helping Children Worldwide is a 501 (c) 3 nonprofit organization | 703-793-9521 | [email protected]

©2017 - 2021 Helping Children Worldwide

All donations in the United States are tax-deductible in full or part. | Donor and Privacy Policy

©2017 - 2021 Helping Children Worldwide

All donations in the United States are tax-deductible in full or part. | Donor and Privacy Policy